It was in light of the decline of the erstwhile USSR that the field of political science plausibly witnessed a debate with regard to the future of global narratives. For a while, the End of History and the Last Man by Dr. Francis Fukuyama appeared to have gathered momentum, whereby it was felt that the world would no longer have history as conventionally inferred, for the very incident signified the prevalence of western democracy and capitalism. It was only a matter of time before the impugnation of his theory arose. It emerged that non-western nations yet retained a paradigm of the world shaped by their special milieus and acted accordingly, and that it was therefore erroneous to expect their acquiescence to the western paradigm of the world or in any way consider it superior to their own.

Amidst the debate arose Samuel Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, in accordance with the contentions of which the period posterior to the Cold War would be characterized with prevalence of conflict grounded in religious and cultural identities. Reflectively, the happenstantial fact that Fukuyama had been Huntington’s student and that the latter’s thesis was in response to the conclusions of the former, was overshadowed by the sheer significance of ideas proffered by them both.

As it happens, human ideas can hardly be perfect, and so it follows that Huntington’s ideas have naturally been revisited. It is apt for the purposes this paper to examine the factors consonant with as well as factors contrary to Huntington’s propositions. Given the potential voluminosity of analysis presupposed by such a topic, it is pertinent, so as to evade abstraction, to suitably define the phraseology that would be ubiquitous in this paper. Needless to say, the most significant word is “Civilization.”

Civilization and their contemporary conformations

Huntington appears to have agreed upon a civilization being the broadest cultural entity. The definition proffered by Immanuel Wallerstein to which Huntington has also alluded closely resembles the latter’s idea of a civilization, who proceeds to cite the former as follows, “Civilization is a particular concatenation of worldview, customs, structures and culture (both material culture and high culture) which forms some kind of historical whole and which coexists (if not always simultaneously) with other varieties of this phenomenon” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips). On that ground, he notes that the civilization to which a person belongs “is the broadest level of identification with which he strongly identifies” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips).

In the contemporary milieu, a civilization may schematically be understood as a nation or an agglomeration thereof which by itself may or may not discharge such functions as a government would, but whose constituent units certainly would. The major civilizations of today are understood to be the Sinic, Japanese, Hindu, Islamic, Orthodox, Western and, subjectively, Latin American and African. Insofar as religions are concerned, the religions of Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism are associated with major civilizations.

The history of civilization as we know it can be traced millennia ago to the Egyptian Civilization; the Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization encompassing much of India, present-day Pakistan and spreading soon after; and the Chinese Civilization. There could be debate as to the precise year of their commencement, but in view of their protracted periods of survival — with the Indian civilization yet being recognized as such — their commencement may schematically be said to be roughly cotemporal with one another, in that the advent of one was not in a different ‘era’ as one may suppose. Indeed, there also were numerous civilizations in other parts of the world thereafter, such as in the American continents.

However, as Huntington aptly notes, contacts between or amongst civilizations throughout a capacious portion of human history were at best intermittent albeit often intense. It is only in the preceding few centuries and thereafter that limited and intermittent encounters paved way for sustained, overpowering, unidirectional impact of the West on all other civilizations. Indeed, as India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru noted in his epochal book Glimpses of World History, the stalwarts of the ancient historical era such as Socrates, Ashoka or Caesar would have noticed a few changes had they appeared through an act of miracle in the early eighteenth century, but would have “as a whole recognized the world” (Nehru, Jawaharlal). However, were they to appear but a century or so thereafter, they would have been greatly benumbed, given the myriad ways in which technology had altered the world, for it was the era of Industrial Revolution which also led to a remarkable change in contact amongst civilizations. It is, therefore, only apt to view the civilizational intricacies keeping the last few centuries into consideration.

Refutation of a Universalist Paradigm

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Cold War concluded, and the popular sentiment amongst numerous academicians for a short period of time was that history in itself had drawn to a close. To their comprehension, history was but a struggle of ideologies, and the Cold War’s conclusion had established the universal victory of liberal democracy throughout the world. On these grounds, the notion of a possible universal civilization gathered momentum, also espoused by the noted author of Indian origin, V.S. Naipaul whom Huntington also alludes to. The universalist paradigm was grounded on three rather facile assumptions, namely:

- Liberal democracy was the only alternative to communism. Huntington presciently noted that the proponents of a universalist paradigm of civilization discounted the other paradigms of nationalism, corporatism and the unique market communism that China was characterized with.

- Increased interaction amongst peoples — trade, investment, tourism, media, electronic communication in general — was generating a common world culture. Indeed, in this era of globalization, newer challenges such as those of terrorism and climate change behove international cooperation which in some measure may warrant compromises on national interest. Huntington, however, noted that social psychology was able to explain the seemingly paradoxical view of increased segregation with increased trade and communications; a phenomenon evident during World War I. He employed the distinctiveness theory, whereby “people define their identity by what they are not. Increased international interaction leads people to increasingly accord greater relevance to civilizational identity” (Huntington, Samuel Phillip).

- A universal civilization is the ineluctable culmination of the broad process of modernization ongoing since the eighteenth century. Huntington, however, noted that the fact that “there exist significant differences between modern and traditional cultures does not necessarily indicate that societies with modern cultures resemble each other more than do societies with traditional cultures” (Huntington, Samuel Phillip). Insofar as increased interaction facilitates rapid transfer of techniques, inventions and practices from one society to another, and insofar as modern society is based on industry whereby the agricultural reliance on local natural environment is lessened, modern societies could conceivably converge. However, the commonality so achieved does not necessarily ensure a coalescence into homogeneity.

- Thus, did Huntington repudiate any possibility of a universal civilization emerging from the tribulations of the Cold War.

Background to Possible Debasement of Western Civilization

The governments of medieval Europe’s myriad nations were highly curious as regards the lands beyond their frontiers, such as the opulent Asian nations of India and China. This was synchronous with the period of the gradual descent of the European feudal classes and the gradual ascent of the entrepreneurial class which would later be termed the bourgeoisie. Jawaharlal Nehru notes in his Glimpses of World History:

“[Marco Polo’s travel accounts] brought home to them the greatness and wealth and marvels of the larger world. It excited their imaginations, and called to their sense of adventure, and tickled their cupidity. It induced them to take to the sea more. Europe was growing. Its young civilization was finding its feet and struggling against the restrictions of the Middle Ages. It was full of energy, like a youth on the verge of manhood” (Nehru, Jawaharlal).

Nehru, Jawaharlal. Glimpses of World History. Penguin Books India, 2005

These were driven chiefly with a mercantilist desire — the increasing monetary power of the capitalist class was soon followed by their influence in their respective governments; the United Kingdom House of Lords in particular. A long era of colonialism thus commenced.

It may be stated that colonialism, in its modern form at any rate, was a western legacy. Huntington notes that while nations did struggle for independence from their colonial oppressors, the colonial experience also exposed them to western culture and ideas, chief among which were the ideas of the rule of law, separation of spiritual and temporal authority, social pluralism, representative bodies such as parliaments and so forth. Keeping the unique circumstances of the colonized nations in view, it is but natural to conclude that the responses to colonialism were not uniform.

Comprehensively, the colonial experience led to three noteworthy reactions so far as the sociocultural spheres are concerned. The first was rejectionism in either full or very substantial measure. This was implemented by Japan. It presciently recognized the perils that the European powers could pose to its culture and sovereignty. Huntington estimates 1542 as the commencement year of Japan’s isolation, which was of course gradual, and lasted well until mid-nineteenth century, when “she opened her door and windows again…she went ahead with a rush, made up for lost time, caught up to the European nations, and beat them at their own game” (Nehru, Jawaharlal).

The second reaction is commonly termed “Kemalism” after Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the first leader of present-day Turkey. He was firm in his insistence on westernization and modernization. This is significant, in that he did not view as important any native approach. To him, modernization alone did not suffice; it had to be accompanied with the adoption of western values, principally those of secularism. He commenced attacking “many other old customs, and was not very courteous in his treatment of religion”, writes Jawaharlal Nehru, and “he wanted no leadership of Islam for his country or for himself.”

The third reaction was reformism, whereby modernization — such as implementation of industrialization — was combined with the preservation of the central values, practices and institutions of the society’s indigenous culture. India, for instance, was characterized chiefly with a non-violent struggle spearheaded by the Indian National Congress, whose principal figures had availed western education, and were faced with the monumental challenge of amalgamating the newly gained knowledge with the positive peculiarities of the Indian sociocultural milieu and eradication of solecisms therein.

The era of the commencement of Cold War was concomitant with a gradual shift of colonized countries towards independence. Arguably, the most momentous was India’s independence in 1947, a crown jewel of the British Empire as it had been. Several such nations made opportune use of the nearly four-and-a-half decades of conflict between Soviet communism and Western capitalism to make rapid economic progress. While it would not be strictly apt to describe the West and in general and the U.S. in particular as declining — for their military power continues advancing — it is certainly beset with a few disadvantages. Huntington notes:

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, the Western share of global manufacturing output rose dramatically, peaking in 1928 at 84.2 percent of world output. Thereafter, the share declined as its rate of growth remained modest. By 1980s, the West accounted for 57.8 percent of global manufacturing output, roughly the share it had 120 years earlier in the 1860s.

Huntington, Samuel Phillips. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Simultaneously, the other nations grew in prosperity. “The erosion of Western culture follows, as indigenous, historically rooted mores, languages, beliefs, and institutions reassert themselves” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips).

Reasons behind cultural resurgence

Huntington alludes to British sociologist Ronald Dore, who explained the cultural resurgence through a phenomenon he termed the Second-Generation Indigenization Phenomenon. It was applicable particularly to China and Japan, but also to other countries that had achieved independence. Huntington quotes him as follows, “The first modernizer or post-independence generation has often received its training in foreign (Western) universities in a Western cosmopolitan language. Partly because they first go abroad as impressionable teenagers, their absorption of Western values and life-styles may well be profound” (quoted in Huntington, 1996). The second generation, however, which is much larger, receives its education in universities in its own homeland, which would have been created by the first generation, and the “local rather than the colonial language is increasingly used for instruction”, which “provide a much more diluted contact with metropolitan world culture.” The graduates of these universities “succumb to the appeals of nativist opposition movements.”

Seeing as culture is inexorably tied with religion, the cultural resurgence can also be attributed to a phenomenon Huntington has termed la revanche de dieu — a global revival of religion concomitant with economic and social modernization itself becoming global in scope. Indeed, it sounds counterintuitive; socioeconomic progress should ideally lead to a gradual decline of religion as scientific temper takes precedence. However, Huntington notes, this was the prevalent wisdom in the first half of the twentieth century. Protracted socioeconomic modernization is the precise reason behind the revival of religion. He notes:

People move from the countryside to the city, become separated from their roots, and take new jobs or no job. They need new sources of identity, new forms of stable community, and new sets of moral precepts to provide them with a sense of meaning and purpose. Religion, both mainstream and fundamentalist, meet these ends.

Huntington, Samuel Phillips. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon & Schuster, 1997.

It is thus vital to note that people do not live by reason alone. They cannot “calculate and act rationally in pursuit of their self-interest until they define their self” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips). Interest politics presupposes identity. Contrary to potential dismissive views at the outset, the questions, “Who am I? Who are we?” indeed matter. Karl Marx, therefore, may have been mistaken when he contended that religion was the opium of the masses; as Regis Debray notes, “Religion is not the opium of the people, but the vitamin of the weak.” Huntington notes that such revival is not itself indicative of a sentiment inimical to modernity; it is only symptomatic of newly confident nations increasingly resisting Western influence.

Potential Clashing Civilizations

Huntington is unambiguous in his assessment that there would be two non-Western civilizations with which the West would clash: the world of Islam and the nation-state of China. However, he has not dwelt overmuch on the possible conflict between the West and China, purportedly owing to an absence of religious sentiment involved in their equation. He insists that the Islamic resurgence in the 1990s was not driven through radically supremacist notions; it was progressive in that it sought modernization but rejected Westernization. He describes this phenomenon nearly ubiquitous in the Islamic world as the “most pervasive and fulfilling” manifestation of la revanche de dieu.

He notes compendiously the pivotal role of students and intellectuals in the Islamic resurgence. He describes three elements which were instrumental. The first was the control of student unions and similar organizations by fundamentalists. The second element composed of urban, middle-class people who gradually developed sympathy for the cause. The third element was quite crucial, for it composed of recent migrants to the cities; crowded into decaying and often primitive slum areas. They “were the beneficiaries of the social services provided by Islamist organizations” with an efficacy that the State apparatus could not match.

Islamists were often supported in the Cold War as bulwarks against communist or hostile nationalist movements potentially detrimental to Western interests. The oil boom of the 1970s also “greatly increased the wealth and power of many Muslim nations and enabled them to reverse the relations of domination and subordination that had existed with the West” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips). Oil wealth was seen as evidence of the superiority of Islam. In addition, there Islamic countries have witnessed a great population growth. Large populations, needless to say, require more resources, and hence “people from societies with dense and/or rapidly growing populations tend to push outward, occupy territory and exert pressure on other less demographically dynamic peoples” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips). Islamic population growth is therefore a major contributing factor to conflicts between Muslims and other peoples, particularly in the Balkans, North Africa and Central Asia.

Crucial to Huntington’s thesis is the idea of a core state, that is, a State in a given civilization which wields tremendous hard and soft power. It “attracts those who are culturally similar and repels those who are culturally different.” In some exceptional situations, some countries may resist the influence of their core states, such as Vietnam’s animus against China — the commonality of Confucian culture notwithstanding.

Huntington notes that while the West does have a core state — namely, the United States, which could well be supported by other cardinal states such as France the and United Kingdom — the Islamic world lacks a core state. At first glance, Saudi Arabia could have been viewed as a core state. However, given the protracted antagonism as well as greater military power of Iran, he impugned the idea of the Saudi core state. In contemporary times, his view is only further validated by Turkey’s increasing assertiveness under Erdogan. He was thus quite prescient in his hypothesis of Turkey being the possible core state of Islam in the future, particularly given the Western patronage it had enjoyed as a member of NATO, notwithstanding its contemporary dilution of relations with the West.

He thereafter proceeds to illustrate the very fundamentals of both Christianity and Islam that could lead to a potential clash, and that the clash could arise both due to differences and similarities. Christianity and Islam are different insofar as the former separates the realm of God and Caesar (king) whereas the latter unites religion and politics. However, both entail conspicuous similarities, namely:

(a) monotheism, owing to which they cannot “assimilate additional deities” and thus “see the world in dualistic us-versus-them terms;

(b) universalism — both religions claim to be the one true faith; and

(c) missionary nature, in that both oblige their adherents to convert non-believers to their “true faith.”

Importantly, Islamic history has never chronicled the Enlightenment that the West was fortunate enough to experience. They are thus more prone to fundamentalist ideals. Huntington proceeds to observe disquieting trends to the extent that as the relationship between the West and the Islamic world is concerned. He notes that protests against anti-Western violence have been totally absent in Muslim societies. “Muslim governments, even the bunker governments friendly to and dependent on the West, have been strikingly reticent in condemning terrorist acts against the West” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips). Similarly, while the European governments and publics were critical of numerous American actions against the USSR and communism during the Cold War, they had largely supported and rarely criticized U.S. actions against “Muslim opponents.” Huntington thus notes, “In civilizational conflicts, unlike ideological ones, kin stand by their kin.” And this assumes significance given that in accordance with the increased relevance of religious and cultural identities as a consequence of socioeconomic modernization, such aesthetics may serve to foster antagonistic sentiments.

Through substantial illustration of data, Huntington showed that Muslims in the early 1990s were “engaged in more intergroup violence than were non-Muslims and two-thirds to three-quarters of intercivilizational wars were between Muslims and non-Muslims.” Therefore, “Islam’s borders are bloody, and so are its innards” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips).

Criticism of Huntington’s Hypothesis

The conspicuous feature of Huntington’s hypothesis is that it has not been attributed with inevitability. He only posits the high possibility thereof. He has also not necessarily depicted a thespian view of a clash; with commodious armies clashing with one another, but he has certainly accentuated the possibility of great fiction between the Islamic world and the West. Nonetheless, there has been objurgation categorized into the epistemological, methodological and ethical spheres as respects his exposition, as noted by Professor of Political Science Deepshikha Shahi.

Epistemological Critique

There are the following principal contestations against Huntington’s thesis:

(A) It does not offer a radically different perspective insofar as it fits in neatly with political realism.

It is prudent to note that the realist theory of international relations views politics as being governed by objective laws that have their roots in unchanging human nature; therefore, it is possible to develop a rational theory that reflects these objective laws. It refuses to identify the moral aspirations of a particular nation with the moral laws that govern the universe. It views the concept of national interest defined in terms of power that saves us from moral excess and political folly. Fundamentally, therefore, it is concerned with rational, objective and unemotional reasons of State actions.

Deepshikha Shahi notes that “the clash of civilizations thesis is dismantled historically as soon as we realize that it is nothing new. It is the same Cold War methodology rebranded for maximum impact, a contrived clash that the US was pursuing for several decades by converting an old ally into foe post-World War Two.” Engin Erdem seems to concur when he notes, “Huntington’s thesis basically depends on orientalist understandings of Islam, in which Islam-the ‘other’- is perceived as culturally inferior to the West and identified as threat and even enemy. This understanding ignores the diversity, plurality and various dynamics of Islam/the Muslim World as well as that of ‘Islamism’ and ‘Islamic fundamentalism.” (Erdem, Engin).

(B) Huntington’s hypothesis is elitist

The objurgation on grounds of elitism was made particularly conspicuous by Deepshikha Shahi. She notes that “the agenda of US elites differs from that of the American masses.” She quotes Michael Winter Dunn, in whose view “the clash of civilizations rhetoric is not limited to American and European elites — many al-Qaida militants also view the current US-led conflicts in the Middle East as a proof of clash between Islam and the West.” She says that the real clash is thus “not between the civilizations but between the elites and the masses over the definition of reality.”

Methodological Critique

Following are the methodological criticisms of Huntington’s hypothesis:

(A) Civilizations, as opposed to being monolithic, have in fact a polycentric structure.

As Fred Halliday notes, Huntington ignores the internal dynamics, plurality and myriad complexities of Islam and the Muslim world. Insofar as Islam has numerous sects and also has a system of differentiation not unlike the caste system in Hinduism, it is indeed not a homogenous whole but a variegated consolidation. Aijaz Ahmad’s contentions state as much when he asserts that, “there is no single Islamic culture, but multiple centres of Islam and various types of political Islam and Islamism in the Muslim world.”

(B) The thesis is reductionist insofar as it is an oversimplification.

Deepshikha Shahi notes that Huntington ignores, “the multiple causes of inter-and intra-national conflict, thereby essentializing the civilizational factor as the prime reason” (Shahi, Deepshikha). She also notes that Huntington reduces the multiple dimensions of individual identity and essentializes the civilization as the chief aspect. She also cites Shireen T. Hunter and Muhammad Asadi to note that “the conflictive relations between the West and the Muslim world hardly stems from civilizational differences but from structural-political and economic inequalities between the two worlds of ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’.”

Ethical Critique

Huntington’s thesis has invited condemnation of its immoral applications.

(A) The thesis was a strategy to influence US foreign and defence policy.

Deepshikha Shashi cites Naz Wasim’s confirmation thereof. In accordance with this argument is Edward Said’s contention cited by her, that “Huntington formulated his thesis while keeping an eye on rivals in the policy making ranks; theorists such as Francis Fukuyama and his ‘end of history’ idea, as well as the legions who had celebrated the onset of globalism and the dissipation of the states.”

She goes on to state, “Interestingly the personal ambition of Huntington was in tandem with the expansionary goals of US policy makers. The declaration of a possibility of World War III by Huntington fit well with the needs of the US arms industry” (Shahi, Deepshikha). Noam Chomsky goes so far as to note that, “every year the White House presents to Congress a statement describing reasons for having a huge military budget. For fifty years, it used the pretext of a Soviet threat. However, after the end of the Cold War, that pretext was gone. Therefore, Huntington constructed the Islamic threat as a pretext to justify the need for maintaining and enhancing the defence-industrial base.” Huntington’s thesis, therefore, “is in fact an enemy discourse that looks for new enemies” (Shahi, Deepshikha).

(B) Huntington’s thesis is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The ethical critique also asserts that it, “causes the expected event to occur, and thus, verifies its own accuracy.” Prof. Shahi goes on to cite John Ikenberry who contends that, “Huntington’s thesis is the civilizational equivalent of the security dilemma, in which misperception about the other eventually increases tension, and then leads to conflict” (Shahi, Deepshikha). In a letter to American neoconservative historian and foreign policy commentator Robert Kagan, Nobel laureate Amartya Sen wrote, “the violent tendency within Islam is not only because of the ‘pull’ of resurgent Islam, but also due to the ‘push’ of distancing coming from the Western parochialism that characterizes Huntington’s thesis.”

Challenges within cleft countries: the Indian experience

The critics have thus far asserted that Huntington’s understanding of Islam was rather perfunctory. Indeed, owing to the myriad conflicts even within the Islamic world, the probability of a homogenous Islamic world clashing with the West is at best remote if not outright impossible. They have also criticized his approach by terming it reductionist insofar as it ignores a multitude of other factors that could cause conflict. Prof. Shahi particularly notes that Huntington had “demonized Islam.” However, so far as citations are concerned, they appear to not employ historical objectivity as respects understanding Islam.

In his hypothesis, Huntington differentiated between core countries and cleft countries. The former, as has been explained, is the prepotent nation in a civilization, whose military, economic and cultural capabilities far exceed those of other nations in the same civilization. The latter, on the other hand, are nations where large groups belong to different civilizations. As Huntington notes, major groups from two or more civilizations in a cleft country effectively say, “We are different peoples and belong in different places.” The most notable example of a cleft nation is India.

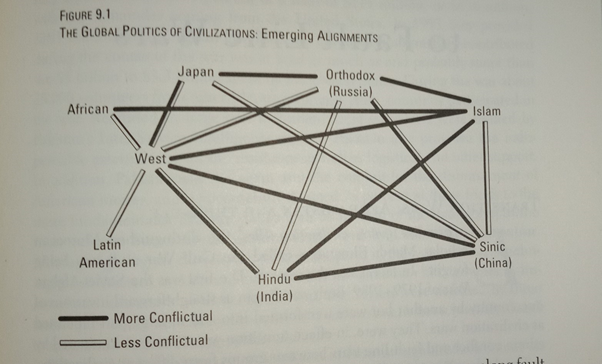

Huntington hypothesizes the possible relationships amongst civilizations in the following manner:

It is interesting to note that Huntington hypothesizes a “more conflictual” relationship between India and the Islamic world. The fact that India is a cleft state in Huntington’s view — with Hindus and Muslims being in sizeable numbers, adds to the possibility of their being conflicts between the two. Primarily, however, the conflict would appear more internal than external; with the external countries at best passing statements of censure as respects India’s “mistreatment of Muslims.” Describing India as a primarily Hindu civilization, he acknowledges the overarching Hindu substratum of the contemporary Indian State; indeed, a modern republic conformation of a millennia-old civilization.

Islam may be said to have been inexorably entwined with the Indian civilization’s sociocultural milieu with its advent in the present-day Indian subcontinent in the seventh century, not through conquests but with the intention of pursuing trade. As Jawaharlal Nehru notes in Glimpses of World History:

The Arabs had friendly relations with the Indian rulers of the south, especially the Rashtrakutas. Many Arabs settled along the west coast of India and built mosques in their settlements. Arab travellers and traders visited various parts of India. Arab students came in large numbers to the northern University of Takshashila or Taxila, which was especially famous for medicine…Many Sanskrit books on mathematics and astronomy were translated into Arabic.

…India was not greatly affected or much changed by this contact with the Arabs. But during this long period, India must have got to know something of the new religion, Islam. Muslim Arabs came and went and built mosques, and sometimes preached their religion, and sometimes even converted people. There seems to have been no objection to this in those days, no trouble or friction between Hinduism and Islam. It is interesting to note this because in later days friction and trouble did arise between the two religions. It was only when in the eleventh century Islam came to India in the guise of a conqueror, sword in hand, that it produced a violent reaction, and the old toleration gave way to hatred and conflict.

Nehru, Jawaharlal. Glimpses of World History. Penguin Books India, 2005.

Even during the medieval era when India saw a few centuries of Islamic rule under the Delhi Sultanate and the subsequent Mughal rule, there seems to have been little evidence indicative of a ubiquitous conflict between Hinduism and Islam at the level of a common citizen. Nehru cites a few travellers from foreign lands who were enthralled with the seamless amalgamation of Muslims into the broad Hindu substratum of India. There was thus an instance of “Indianization” among Muslims, even the Mughal emperors themselves, who severed ties with the Caliph. The conflict between Hindus and Muslims was accentuated principally during the colonial era, such as through the introduction of separate electorates so as to foster emotional fissures. However, the historical events bear more sinuosity than the simplistic presumption of the colonial regime being chiefly responsible for fissures between Hindus and Muslims.

Huntington was not the only scholar to have been concerned with the assuetude of Islam to engage in conflict. Nearly seven and a half decades ago, the Indian constitutionalist, economist and jurist Dr. B.R. Ambedkar also noted:

“Islam is a close corporation and the distinction that it makes between Muslims and non-Muslims is a very real, very positive and very alienating distinction. The brotherhood of Islam is not the universal brotherhood of man. It is brotherhood of Muslims for Muslims only. There is a fraternity but its benefit is confined to those within that corporation. For those who are outside the corporation, there is nothing but contempt and enmity. The second defect of Islam is that it is a system of social self-government and is incompatible with local self-government, because the allegiance of a Muslim does not rest on his domicile in the country which is his but on the faith to which he belongs. To the Muslim ibi bene ibi patria (where it is well with me, there is my country) is unthinkable. Wherever there is the rule of Islam, there is his own country. In other words, Islam can never allow a true Muslim to adopt India as his motherland and regard a Hindu as his kith and kin. That is probably the reason why Maulana Mahomed Ali, a great Indian but a true Muslim, preferred to be buried in Jerusalem rather than in India.”

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Pakistan: or, The Partition of India. Thacker, 1946.

Seeing as such views could be deemed overly polemical in the contemporary era, Dr. Ambedkar’s claims must be examined in greater detail.

In the First World War, the British had defeated Turkey, which eventually led to the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. The sultan of Turkey happened to be the religious head of the Muslims all around the world, or the Khalifa or caliph, and the British succeeded in deposing him. Inexplicably, while no other Islamic nation across the world appeared disquieted about the same, leading Muslims in India appeared particularly agitated, and commenced petitioning the colonial regime, demanding that the caliph be reinstated. This agitation was known as the Khilafat movement. But it is, in fact, a fallacy to say that the Khilafat was started by the Muslims of India as a movement. There was formed only a Khilafat committee, consisting of Maulana Mohammad Ali (not to be confused with Jinnah), his brother Maulana Shaukat Ali, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Hakim Ajmal Khan, Mukhtar Ahmad Ansari and others. It was Gandhi, who was to soon become the principal figure of the national body that spearheaded the Indian national movement for freedom, namely the Indian National Congress, whose support turned it into a movement.

Dr. Ambedkar notes:

The objective of the movement was two-fold: to preserve the Khilafat and to maintain the integrity of the Turkish Empire. Both these objectives were unsupportable. The Khilafat could not be saved simply because the Turks, in whose interest this agitation was carried on, did not want the Sultan. They wanted a republic, and it was quite unjustifiable to compel the Turks to keep Turkey a monarchy when they wanted to convert it into a republic. It was not open to insist upon the integrity of the Turkish Empire because it meant the perpetual subjection of the different nationalities to the Turkish rule and particularly of the Arabs, especially when it was agreed on all hands that the doctrine of self-determination should be made the basis of the peace settlement.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Pakistan: or, The Partition of India. Thacker, 1946.

In the words of historian Dr. Vikram Sampath, Gandhi never made clear why this (supporting the Khilafat) “should be a priority only for the Indian Muslim community when their co-religionists from other parts of the Muslim world were themselves unperturbed by the dissolution of the caliphate. When Turkey itself favoured such a move, and when none of this made anyone in the Muslim world less honourable or disrespectful of their faith in the Prophet, why was such an assumption being made on behalf of only the Indian Muslims?” (Sampath, Vikram). He notes that Gandhi had made two very tall promises to the Indians: that within one year, provided the Hindus and the Muslims stayed united, he could bring them both Swaraj and the reinstation of the Caliph.

When, of course, none of the promises materialized, the mobilized Muslims lost their patience. Then began a series of sporadic riots between the Hindus and the Muslims that would continue almost unabated for fifteen long years, as Dr. Ambedkar notes in benumbing detail through government data. He describes one such particularly heinous event as follows; perhaps among the first ones in the said spell of fifteen years:

Beginning with the year 1920 there occurred in that year in Malabar what is known as the Mopla Rebellion. It was the result of the agitation carried out by two Muslim organizations, the Khuddam-i-Kaba (servants of the Mecca Shrine) and the Central Khilafat Committee. Agitators actually preached the doctrine that India under the British Government was Dar-ul-Harab and that the Muslims must fight against it and if they could not, they must carry out the alternative principle of Hijrat. The Moplas were suddenly carried off their feet by this agitation. The outbreak was essentially a rebellion against the British Government The aim was to establish the kingdom of Islam by overthrowing the British Government. Knives, swords and spears were secretly manufactured, bands of desperadoes collected for an attack on British authority. On 20th August a severe encounter took place between the Moplas and the British forces at Pinmangdi Roads were blocked, telegraph lines cut, and the railway destroyed in a number of places. As soon as the administration had been paralyzed, the Moplas declared that Swaraj had been established. A certain Ali Mudaliar was proclaimed Raja, Khilafat flags were flown, and Ernad and Wallurana were declared Khilafat Kingdoms. As a rebellion against the British Government it was quite understandable. But what baffled most was the treatment accorded by the Moplas to the Hindus of Malabar. The Hindus were visited by a dire fate at the hands of the Moplas. Massacres, forcible conversions, desecration of temples, foul outrages upon women, such as ripping open pregnant women, pillage, arson and destruction — in short, all the accompaniments of brutal and unrestrained barbarism, were perpetrated freely by the Moplas upon the Hindus until such time as troops could be hurried to the task of restoring order through a difficult and extensive tract of the country. This was not a Hindu-Moslem riot. This was just a Bartholomew. The number of Hindus who were killed, wounded or converted, is not known. But the number must have been enormous.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Pakistan: or, The Partition of India. Thacker, 1946.

It is well for the sake of brevity to not enumerate the minutiae of all such events, which eventually culminated in the Partition. But the Khilafat movement certainly had two momentous lessons: (a) that mobilization on grounds of Islam sufficed to engender a sentiment of unity, the division into castes notwithstanding; and (b) that Islamist sentiment was antithetical to Indian nationalism. The latter point is confirmed by Dr. Ambedkar himself:

Among the tenets one that calls for notice is the tenet of Islam which says that in a country which is not under Muslim rule, wherever there is a conflict between Muslim law and the law of the land, the former must prevail over the latter, and a Muslim will be justified in obeying the Muslim law and defying the law of the land.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Pakistan: or, The Partition of India. Thacker, 1946.

He adds:

According to Muslim Canon Law the world is divided into two camps, Dar-ul-Islam (abode of Islam), and Dar-ul-Harb (abode of war). A country is Dar-ul-Islam when it is ruled by Muslims. A country is Dar-ul-Harb when Muslims only reside in it but are not rulers of it. That being the Canon Law of the Muslims, India cannot be the common motherland of the Hindus and the Musalmans. It can be the land of the Musalmans — but it cannot be the land of the ‘Hindus and the Musalmans living as equals.’ Further, it can be the land of the Musalmans only when it is governed by the Muslims. The moment the land becomes subject to the authority of a non-Muslim power, it ceases to be the land of the Muslims. Instead of being Dar-ul-Islam it becomes Dar-ul-Harb.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Pakistan: or, The Partition of India. Thacker, 1946.

He thereafter proceeds to warn that such a view must not be supposed to be of academic interest alone, for “it is capable of becoming an active force capable of influencing the conduct of the Muslims. It did greatly influence the conduct of the Muslims when the British occupied India” (Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji). He further notes:

A third tenet which calls for notice as being relevant to the issue is that Islam does not recognize territorial affinities. Its affinities are social and religious and therefore extraterritorial…This is the basis of Pan-Islamism.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Pakistan: or, The Partition of India. Thacker, 1946.

The remainder of Dr. Ambedkar’s book is a lucid illustration of the capitulation by the Indian National Congress, to increasingly aggressive demands by the political representatives of the Islamic community; and how the colonial regime was only too glad to oblige. It would, of course, be irrational to suppose that the Islamist sentiment had ubiquitous support. Some influential Shia Boards had opposed the Khilafat movement, affirming their loyalty to the Government of British India, as did Mohammad Ali Jinnah prior to becoming the principal figure of the Muslim League. However, seeing as the Muslim League, as noted by Dr. Ambedkar, secured stupendous victories in the elections of mid-1940s in Muslim-majority districts and provinces, it could reasonably be said that the Islamist sentiment at that point in time received substantial support. Contrary to popular notions, the Indian National Congress was therefore not so popular amongst the Muslims.

It would also be gratuitous of us to analyze current trends strictly through past events. However, the past provides a context to the present — it would be impolitic of us to overlook the eventual sanguinary Partition of India on religious grounds. Yet, the government of post-independence India appeared to have learnt nothing from the Partition experience. Authors Harsh Madhusudan and Rajeev Mantri note in their epochal book, “A New Idea of India: Individual Rights in a Civilisational State”:

Despite the carving out of Pakistan (and what is now Bangladesh) in the name of political Islam, and the secessionist insurgency seen in Kashmir due to similar motivations, so-called secular India did not adopt common personal laws. This happened even though Nehru changed, and rightly so, the Hindu personal laws by passing the Hindu code bills in 1955–1956. While the Hindu laws were made progressive, Muslim laws were left untouched.

Madhusudan, Harsh, and Rajeev Mantri. A New Idea of India: Individual Rights in a Civilisational State. Westland Publications Private Limited, 2020.

They also note:

Thanks to increased economic freedom since 1991, there are increasing numbers of Muslims who see themselves, first and foremost, as aspirational Indians. But ultra-conservative Islamist leaders and ‘secular’ politicians, who are invested in denying the individuality of the Indian Muslim for maintaining their power, want to box these individuals into a group identity. The mentality that seeks to view Muslims as a separate group in free India also thrusts upon them a separate civil code, once again in the name of an Orwellian kind of secularism.

Madhusudan, Harsh, and Rajeev Mantri. A New Idea of India: Individual Rights in a Civilisational State. Westland Publications Private Limited, 2020.

They proceed to note in piercing detail the national government’s propensity to formulate policies that capitulate to the regressive yet vocal factions amongst India’s Muslim population — not very different from the grudging but evident capitulation by the Congress to the Muslim League in the days of the Raj. Interestingly, they do not proceed to hypothesize another partition; they do not in their book propose that the Muslim community would therefore become more Islamist.

However, they do acknowledge a certain unrest amongst India’s Hindu population, that expresses itself in a cultural nationalist resurgence in the contemporary era. They note the clarity of one phenomenon, that “the increasing feeling of revulsion towards the minoritarianism of the Indian State is resulting in pushback from members of the majority community” (Madhusudan, Harsh and Rajeev Mantri).

The rather prolix historical account of the relationship between Hindus and Muslims serves to validate Huntington’s concerns as regards a cleft state wherein two groups from different civilizations assert their distinct identity; to the possible extent of defining themselves as two separate people. This was seen during the colonial experience when India was partitioned on religious grounds. The contemporary relationship, while significantly better than that from several decades ago, leaves much to be desired. As Huntington himself had noted, the great changes of the first half of the twentieth century led to a general trend towards secularization. This could be attributed to the sweeping changes brought about by industrialization, which invariably results in the gradual effacement of old social structures such as the effacement of feudalism in Europe, and a gradual withering away of the Church authority. However, India could not industrialize to a sufficient extent. The old structures of religion and caste were thus not adequately replaced with newer structures that would be in greater congruity with modern times.

Conclusions

Thus, insofar as Huntington’s thesis hypothesizes instability within cleft states wherein culture is under great distress, it is valid. As a matter of fact, he raises concerns as respects the possibility of the United States turning into a cleft country itself. He noted that the issue that warranted concern was “whether Europe and America will become cleft societies encompassing two distinct and largely separate communities from two different civilizations, which in turn depends on the numbers of immigrants and the extent to which they are assimilated into the Western cultures prevalent in Europe and America” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips). He cites an observer in whose opinion, the fact that the United States was a country built by immigrants notwithstanding, “most Americans perhaps saw their nation as a European-settled country, whose laws were an inheritance from England, whose language was and should remain English, whose institutions and public buildings find inspiration in Western classical norms, whose religion has Judeo-Christian roots, and whose greatness initially arose from the Protestant work ethic.” So far as the polls in the 1990s were concerned, 60 percent or more of the public favoured reduced immigration.

As Huntington notes, much the same sentiment has been seen in Europe, to a surprisingly greater degree. Curiously, while most other immigrants such as Indians or other Asians have assimilated into European societies, Muslims have had considerable difficulty in doing so — France in particular. He therefore notes that Muslims indeed posed an immediate problem to Europe. No other incident as the recent killing of Samuel Paty evinced the same, thus according Huntington’s observation with a degree of prescience. The United States faced similar problems not from Muslims, but from Mexican immigrants. This is bolstered by the rise of the multiculturalist paradigm in the United States. Huntington notes that a small but influential number of intellectuals and publicists in the U.S. have in the name of multiculturalism “attacked the identification of the United States with Western civilization, denied the existence of a common American culture and promoted racial, ethnic, and other subnational cultural identities and groupings.” The problem, Huntington says, is that a multicivilizational United States would not be the United States; it would be the United Nations. Coupled with the fact that U.S. leaders had done little to accommodate diversity by means of assimilation and instead promoted it assiduously at the expense of unity, a sense of coherence could thus be lost. “The multiculturalists also challenged a central element of the American Creed, by substituting for the rights of individuals the rights of groups, defined largely in terms of race, ethnicity, sex and sexual preferences” (Huntington, Samuel Phillips).

The claim that Huntington employed contumelious terms for Islam is invalid in light of an abundance of Islamic history, the Indian example in particular. Invalidating it is Huntington’s own observation that the Islamic resurgence immediately post the end of the Cold War was not guided by parochial factions, but by those that sought modernization, as illustrated earlier. The criticism of his thesis that it served to uphold the interests of the military industry in the U.S. as stated by Noam Chomsky also appears invalid. That there exists a military-industrial complex in the United States is a fact only too well-known. However, he has not expressly endorsed military intervention so as to defend Western interests. And in light of increased Islamism as well as global resurgence of nationalism in the post-9/11 world, Huntington’s thesis merely appears as a prescient warning in advance.

Indeed, a clash is not inevitable, and he acknowledged as much. As a matter of fact, recent trends within various countries appear to indicate that the world may not so much witness a clash amongst core states of different civilizations as within core states themselves, owing to a gradual shift towards their status as cleft countries. It is also true that he did not adequately take into account myriad other factors of conflict; principally the economic ones. However, the increasing relevance of cultural identities in the contemporary world warrant a scrupulous consideration of his inferences, for ultimately, it is the civilizational narrative would appeal to the masses.

WORKS CITED

Ahmad, Aijaz 2008 ‘Islam, Islamisms and the West’, Socialist Register

Amartya Sen, letter to Robert Kagan, ‘Is there a Clash of Civilizations?’, Slate Magazine

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Pakistan: or, The Partition of India. Thacker, 1946.

Chomsky, Noam. “Clash of Civilizations?” Seminar (Magazine), Seminar, http://www.india-seminar.com/2002/509/509 noam chomsky.htm.

Erdem, Engin. (2002). The ‘Clash of Civilizations’: Revisited after September 11. Alternatives — Turkish Journal of International Relations. 1. 81–107.

Halliday, Fred 1996 Islam and the Myth of Confrontation, St. Martin’s Press, p 217.

Huntington, Samuel Phillips. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Kung, Hans ‘Inter-Cultural Dialogue Versus Confrontation’ in Schmiegleow, Henrik (ed) 1999 Preventing the Clash of Civilizations: A Peace Strategy for the Twenty-First Century, St. Martin’s Press, p 103.

Madhusudan, Harsh, and Rajeev Mantri. A New Idea of India: Individual Rights in a Civilisational State. Westland Publications Private Limited, 2020.

Nehru, Jawaharlal. Glimpses of World History. Penguin Books India, 2005.

Sampath, Vikram. Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past, 1883–1924. Penguin Viking, 2019.

Shahi, Deepshikha. “The Clash of Civilizations Thesis: A Critical Appraisal.” E-International Relations, 2 Apr. 2017, www.e-ir.info/2017/04/02/the-clash-of-civilizations-thesis-a-critical-appraisal/.